of better yoga with props

by Anthony Carroccio

(July/August 1998, Healing Retreats & Spas)

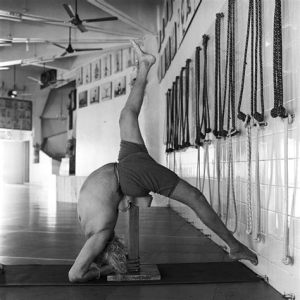

The fiery Indian genius of the yoga posture is considered the father of ‘props.’

The fiery Indian genius of the yoga posture is considered the father of ‘props.’

I have been practicing yoga for thirty years, and like every good student of yoga, I want to continue to learn and improve. Having really good yoga instruction is definitely a plus—and so is taking advantage of yoga-gear called ‘props.’ Props can be anything from found objects to state-of-the-art yoga equipment. Thirty years ago (1958), B.K.S. Iyengar, the internationally renowned yoga master, referred to his then-little-know props as ‘helpers,’ ‘supporters,’ and ‘weight bearers.’ Later he would call them “guides for self learning.” Now, many years later, props are well known and used in every continent.

Iyengar, author of Light on Yoga, Light on Prāṇāyāma, and The Tree of Life, developed and introduced a method of teaching that is precise and vigorous. In a seventieth birthday tribute (1988), Iyengar’s students offered a fond and descriptive thank you to their teacher: “For you to have the merry mischief of a schoolboy, the enthusiasm and virility of youth, and the mature judgment of old age… [you are] the salt of the earth… If salt is present, can pepper be far behind? You always keep your pupils on their toes, lest you raise your expressive eyebrows and unleash your peppery temper against them and their lack of total attention and inefficient participation.“

This fiery Indian genius of the yoga posture is considered the father of props. Most every use or manifestation of yoga gear has descended through the sphere of his influence. He does mention his guru using rings and rope, but Iyengar alone is responsible for introducing the use of chairs, bricks, slanting planks, bolsters, boxes, belts, walls, and more.

Using the Limbs of My Body

Using the Limbs of My Body

When he began teaching in India in 1938, Iyengar noticed that his pupils had difficulty doing the postures, “I realized that raw students or patients [referred by medical professionals] could not derive maximum advantage. In the beginning, I used to attend each individual using the limbs of my body to support, to teach the pupils to get the effect of an āsana.” Iyengar relates how in the beginning , “I used to pick up sticks and bricks lying in the roads and use them to make progress in my mastery of āsana [yoga postures]. Though crude, they were helping me get a grip on the āsana.” He understood early in his career the significance of his ‘helpers.’

Necessity is the ‘father’ of invention. In a 1988 interview, Iyengar recalled an experience with his very first pupil [who required propping]: “In 1938, the ex-principal of Fergusson College, Professor Rajawade, was 85 years old. He was suffering from dysentery, and was not even able to walk. At the insistence of Dr. V.B. Gokhale, I began teaching him.“

“He became my guru for inventing methods for teaching invalids. My first innovation came on account of this principal, Rajawade. Just as one lies down to do Śavāsana [corpse pose], I made him do Supta trikoṇāsana [triangle pose in a supine position]. First, I separated his legs. Second, I moved the trunk to one side, and then, stretched his hands sideways, as one does in standing trikoṇāsana… This original thinking to find new ways continues even now, to help both healthy and unhealthy people.“

Here, were it not for using the floor as a prop, the benefits of yoga would have been beyond the grasp of one in dire need. Yet, for all his insight and diligence in using props to teach students more effectively, he received the unflattering nickname of “The Furniture Yogi” from the fussy (though perhaps less precise) yoga establishment. Iyengar’s intense personality combined with such criticism probably helped speed the presence of props into the world of yoga. No doubt the challenge likely made him more persistent.

On this point, Iyengar recounts, “Some of the schools do not recommend this kind of assistance. The teachers stand away from pupils and guide theoretically. But I use [props] to assist the [students] physically, subjectively, directly.” In only a few decades (a remarkably short period of time, given the 4,000-year history of yoga*), Iyengar’s innovative approach has profoundly influenced the way haṭha yoga is taught, practiced, and understood.

On this point, Iyengar recounts, “Some of the schools do not recommend this kind of assistance. The teachers stand away from pupils and guide theoretically. But I use [props] to assist the [students] physically, subjectively, directly.” In only a few decades (a remarkably short period of time, given the 4,000-year history of yoga*), Iyengar’s innovative approach has profoundly influenced the way haṭha yoga is taught, practiced, and understood.

Today it is virtually impossible to see yoga postures being taught without the presence of at least one yoga prop—the ‘sticky mat.’ Iyengar’s profound insight into the fundamentals of yoga postures dictated the need for a firm, nonslip surface on which to develop stable, anatomically correct form. The sticky mat is now considered an essential prop**.

Taking It to the Next Level

For years I practiced without props because that is all I knew. Although yoga was an important part of my life, my progress was slow, and I was often frustrated by the lack of improvement. Even after twenty years, my yoga shtick remained pretty much the same. This all changed when I took a six-week class in 1988. It was a great class because there were only ten students—more intimate than most. Occasionally, we would meet outside class to practice together. A fellow student invited me to her house. One bedroom was her yoga room. I was amazed: I never imagined that such yoga stuff existed. She had bolsters, benches, a pelvic swing, sandbags, the works. She showed me ways to modify the postures to focus on strength, extension, and alignment***. I realized that it was possible to improve aspects of a posture without creating other bad habits at the same time.

New yoga students today may start out with a sticky mat, a six-foot belt, and a pair of foam or wooden blocks. When they get more serious, they find a wealth of Iyengar inspired gear available to further their yoga practice, everything from folded blankets, shoulderstand lifts, and back-bending benches, to new and exciting props that take Iyengar’s ‘helpers’ to the next level in their evolution.

A Rich and Tangible Process

A Rich and Tangible Process

Recently, I asked Frederic Ferri, a yoga teacher and the developer of the YogaPro system of props, for his western perspective. “Iyengar’s contribution to teaching and learning yoga postures accomplished several important things all at once,” says Ferri. “It gave students a direct way to connect with each posture as a rich and tangible process not just a routine or fixed goal.” Ferri also believes that Iyengar clearly demonstrated the effectiveness of starting at the beginning and working with the anatomical principles that comprise all yoga postures. This helped to take emphasis off of trying to mimic other people’s model postures.

Iyengar himself recounts his early days teaching yoga in India. “I compared a lot of āsana in books. The śīrṣāsana [headstand] of one person was different from that of another. Each āsana was illustrated differently. I thought that the practitioners must be presenting them according to their whims and fancies. Doubts and confusion led me to experiment with all their presentations to find out, by trial and error, which were the wrong, which were the right ways.“

Iyengar’s props gave every yoga teacher and student an immediate means of realizing and working with the precision of their own bodies. Starting with an objective and logical approach to the postures makes learning yogāsana more accessible, meaningful, and manageable. Says Ferri, “Iyengar brought yoga from a distant and mystical India and placed its vast potential squarely on our doorstep.“

Learning to Swim While Looking Toward the Shore

Learning yogāsana in the absence of props could be compared to learning to swim while looking toward the shore, watching someone demonstrate their best stroke, versus having a teacher or a float in the water with you, supporting you and helping you precisely when and where you need it. Ferri explains, “All yoga postures are made up of the same basic components. Bodies have the same parts and the same agency and manner of movement. We interact precisely with the laws of gravity, physics, and biomechanics. Learning position, balance, and movement is so much easier if these natural laws are available to assist us rather than control us.” And props, in the water or on dry land, helps us do just that.

A current prejudice about props from the purists’ point of view is that you need nothing external to do yogāsana and prāṇāyāma. Perhaps they suspect the external props would somehow interfere with the inward journey. However, a change in consciousness is not dependent on the absence of external stimuli. I find my awareness is enhanced by using props. External assistance can increase the quality of internal awareness and magnify consciousness.

Use of Props and Cheating

Use of Props and Cheating

For others, a question still lingers—is using props cheating? In fact, the opposite is more often the case. One of the prominent features of props is that they disallow cheating. The body will cheat all by itself, without our having any awareness of it. It prefers its old ways. But props focus attention on form, which in turn helps us discover and use parts of our bodies that haven’t been participating.

The physical precision with which yogāsana are practiced produces many of the nonphysical benefits that arise: calm, focus, tolerance, discipline, wisdom, and spiritual strength. Props provide the form and feedback that help bring about these results. Yogāsana and prāṇāyāma, like most things, are both challenging and more rewarding when done correctly.

While all roads ultimately lead to Rome, the paths do vary. Some are smooth, some are rocky—some take the longer way, others are more direct. If learning haṭha yoga is where you’re heading, props are an excellent way to go.

* Iyengar and the Invention of Yoga

*** Iyengar Method