Restraints Abound

Most drivers are required to stay on the right side on two-way roads, yet others have to do so on the left. While on these roads we need to observe speed limits, turn lanes, detours, etc. Similarly, our cupboards separate our dishes and kitchenware. Some civil privileges such as voting require a minimum age, just as does retirement. The trades and professionals have parameters that need to be heeded. Recuperation sometimes comes with an extensive list of restrictions. Almost all begin education at a required age, and in this country are expected to graduate HS, at a minimum. Fewer still continue on, and achieve their terminal degrees in another 2-8 years.

A select few pursue self-development, while imposing additional restrictions. In this regard, we seek the advice of those who’ve already traveled this path. Bellur Kṛṣṇamachar Sundararaja Iyengar was such a guide for close to 1,000 certified Iyengar Method instructors in the US, with only a half-dozen of these residing in KS. Even after death, Mr. Iyengar continues to point the way via numerous writings. His pursuit was noteworthy. At 16, beginning āsana studies with his brother-in-law, the renown Śri Tirumalai Kṛṣṇamacharya, in Mysore. When 18, young Sundararaja was assigned to instruct in Pune, where he continued in his inquiry ’til the age of 95.

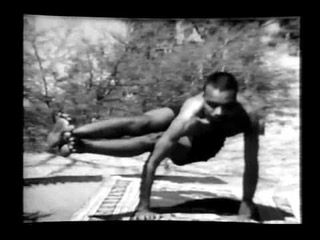

BKS himself followed his teacher’s example, resisting the traditional path, and eventually becoming a householder. There is film of Sundararaja when twenty practicing the vinyāsa of his lineage. This third part, (āsana) of Patañjali’s aṣṭāṅgayoga (eight limbs of yoga) would often consume about 10 hrs each of these early days.

Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtras

In his pursuit, BKS eventually develop what his students endearingly came to call the Iyengar method of yoga. In time he wrote Light on the Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali, and later Core of the Yoga Sūtras. “As a mortal soul, it is a bit of an embarrassment for me with my limited intelligence to write on the immortal work of Patañjali on the subject of yoga.”

“Patañjali fills each sūtra with his experiential intelligence, stretching it like a thread (sūtra), and weaving it into a garland of pearls of wisdom to flavour and savour by those who love and live in yoga, as wise-[beings] in their lives. Each sūtra conveys the practice as well as the philosophy behind the practice, as a practical philosophy for aspirants and seekers (sādhakas) to follow in life.”

Patañjali begins his four-chapter (I-IV) sūtra compilation thusly, I.1, atha yogānuśāsanam, Now the teachings of yoga [are presented]. He then summarises in I.2, yogaś citta-vṛtti-nirodhaḥ, Yoga is the stilling of the changing states of mind.

“Yoga is defined as restraint of fluctuations in the consciousness. It is the art of studying the behaviour of consciousness, which has three functions: cognition, conation or volition, and motion. Yoga shows ways of understanding the functionings of the mind, and helps to quieten their movements, leading one towards the undisturbed state of silence which dwells in the very seat of consciousness. Yoga is thus the art and science of mental discipline through which the mind becomes cultured and matured.”

“As the [changing states of the mind] must be restrained through the discipline of yoga, yoga is defined as citta vṛtti nirodhaḥ. A perfectly subdued and pure citta is divine, and at one with the soul.”

“Patañjali’s opening words are on the need for a disciplined code of conduct to educate us towards spiritual poise and peace under all circumstances. He defines yoga as the restraint of citta, which means consciousness. The term citta should not be understood to mean only the mind. Citta has three components: mind (manas), intelligence (buddhi), and ego (ahaṁkāra), which combine into one composite whole. The term ‘self’ represents a person as an individual entity. Its identity is separate from mind, intelligence, and ego depending upon the development of the individual.”

“Before describing the principles of yoga, Patañjali speaks of consciousness and the restraint of its movements.”

“Why did Patañjali begin the Yoga Sūtras with a discussion [in the first chapter] of so advanced a subject as the subtle aspect of consciousness? We may surmise that intellectual standards and spiritual knowledge were then of a higher and more refined level than they are now, and that the inner quest was more accessible to his contemporaries than it is to us.”

“The verb cit means to perceive, to notice, to know, to understand, to long for, to desire, and to remind. As a noun, cit means thought, emotion, intellect, feeling, disposition, vision, heart, soul, Brahman. Cinta means disturbed or anxious thoughts, and cintana means deliberate thinking. Both are facets of citta.”

“Abhyāsa (practice) is the art of learning that which has to be learned through the cultivation of disciplined action. This involves long, zealous, calm, and persevering effort. Vairāgya (detachment or renunciation) is the art of avoiding that which should be avoided. Both require a positive and virtuous approach.”

“Tapas is a burning desire for ascetic, devoted sādhanā (practice/quest), through yama, niyama, āsana, and prāṇāyāma, [the first four of Patañjali’s eight limbed system]. This cleanses the body and senses (karmendriya and jñānendriya), and frees one from afflictions (klesa nivṛtti).“

“Steady and Comfortable”

Although the Iyengar method revolves about the core of yogāsana, little is said about these in the Yoga Sūtras (195 sūtras according to Vyāsa and Kṛṣṇnamacharya, and 196 according to others, including BKS Iyengar). First mentioned in II.29, yama-niyamāsana-prāṇāyāma-pratyāhāra-dhāraṇā-dhyāna-samādhayo ‘ṣṭav ańgāni, The eight limbs are abstentions, observances, posture, breath control, disengagement of the senses, concentration, meditation, and absorption.

Then on II.46, sthira-sukham āsanam, Posture should be steady and comfortable. Followed by II.47, prayatna-śaithilyānanta-samāpattibhyām, [such posture should be attained] by the relaxation of effort led by absorption in the infinite.

Continuing in II.48, tato dvandvānabhighātaḥ, From this, one is not afflicted by the dualities of opposites. Finally in II.49, tasmin sati śvāsa-praśvāsayor gati-vicchedaḥ prāṇāyāmaḥ, When that [āsana] is accomplished, prāṇāyāmaḥ, breath control, [follows]. This consists of the regulation of the incoming and outgoing breaths .

“Today, the inner quest and the spiritual heights are difficult to attain through following Patañjali’s earlier expositions. We turn, therefore, to [the second] chapter, in which he introduces kriyāyoga, the yoga of action. Kriyāyoga gives us the practical disciplines needed to scale the spiritual heights. My own feeling is that the four padas (chapters) of the Yoga Sūtras describe different disciplines of the practice, the qualities and aspects of which vary according to the development of intelligence and refinement of consciousness of each sādhaka (seeker/aspirant).”

“Sādhana is a discipline undertaken in the pursuit of a goal. Abhyāsa is repeated practice performed with observation and reflection. Kriyā, or action, also implies perfect execution with study and investigation. Therefore, sādhana, abhyāsa, and kriyā all mean one and the same thing.

“Āsana [is] the positioning of the body as a whole with the involvement of the mind and soul. Āsana has two facets, pose and repose. Pose is the artistic assumption of a position. ‘Reposing in the pose’ means finding the perfection of a pose and maintaining it, reflecting in it with penetration of the intelligence and with dedication. When the seeker is closer to the soul, the āsanas come with instantaneous extension, repose, and poise. In the beginning, effort is required to master the āsanas. Effort involves hours, days, months, and several lifetimes of work.”

“When effortful effort in an āsana becomes effortless effort, one has mastered that āsana. In this way, each āsana has to become effortless. While performing the āsanas, one has to relax the cells of the brain, activate the cells of the vital organs, and of the structural and skeletal body. Then intelligence and consciousness may spread to each and every cell. The conjunction of effort, concentration, and balance in āsana forces us to live intensely in the present moment, a rare experience in modern life. This actuality, or being in the present, has both a strengthening and a cleansing effect: physically in the rejection of disease, mentally by ridding our mind of stagnated thoughts or prejudices; and, on a very high level where perception and action become one, by teaching us instantaneous correct action; that is to say, action which does not produce reaction. On that level we may also expunge the residual effects of past actions.”

All Encompassing Restraint

It is this all encompassing effort in the Iyengar method which involves not only the other first four limbs (yama, niyama, āsana, and prāṇāyāma) while in yogāsana, but also the three that follow (pratyāhāra, dhāraṇā, and dhyāna).

“…whatever āsana is performed, it should be done with a feeling of firmness, steadiness and endurance in the body; goodwill in the intelligence of the head, and awareness and delight in the intelligence of the heart. This is how each āsana should be understood, practised, and experienced. Performance of the āsana should be nourishing and illuminative. Some have taken this sūtra [II.47] to mean that any comfortable posture is suitable. If that were so, these would be āsanas of pleasure (bhogāsanas), not yogāsanas. This sūtra [II.47] defines the perfected āsana.”

“From the very first sūtra Patañjali demands the highest quality of attention to perfection. This discipline and attention must be applied to the practice of each āsana, to penetrate to its very depths in the remotest parts of the body. Even the meditational āsana has to be cultivated by the fibres, cells, joints, and muscles, in cooperation with the mind. If āsanas are not performed in this way they become stale and the performer becomes diseased (a rogi) rather than a yogi.”

“Nor does āsana refer exclusively to the sitting poses used for meditation. Some divide āsanas into those which cultivate the body and those which are used in meditation. But in any āsana the body has to be toned and the mind tuned so that one can stay longer with a firm body and a serene mind.”

“Āsanas should be performed without creating aggressiveness (ahiṃsā) in the muscle spindles or the skin cells. Space must be created between muscle and skin so that the skin receives the actions of the muscles, joints, and ligaments. The skin then sends messages to the brain, mind, and intelligence which judge the appropriateness of those actions.”

“In this way, the principles of yama and niyama are involved and action and reflection harmonise. In addition the practice of a variety of āsanas clears the nervous system, causes the energy to flow in the system without obstruction and ensures an even distribution of that energy during prāṇāyāma.”

“Usually the mind is closer to the body and to the organs of action and perception than to the soul. As āsanas are refined they automatically become meditative as the intelligence is made to penetrate towards the core of being. Each āsana has five functions to perform. These are conative, cognitive, mental, intellectual, and spiritual.”

“Conative action is the exertion of the organs of action. Cognitive action is the perception of the results of that action. When the two are fused together, the discriminative faculty of the mind acts to guide the organs of action and perception to perform the āsanas more correctly; the rhythmic flow of energy, and awareness is experienced evenly and without interruption both centripetally, and centrifugally, throughout the channels of the body. A pure state of joy is felt in the cells and the mind. The body, mind, and soul are one. This is the manifestation of dhāraṇā, and dhyāna, in the practice of an āsana.”

“Patañjali’s explanation of dhāraṇā [concentration] and dhyāna [meditation] in the sūtras beautifully describes the correct performance of an āsana. He [writes], ‘the focusing of attention on a chosen point or area within the body as well as outside is concentration (dhāraṇā).’ Maintaining this intensity of awareness leads from one-pointed attention to non-specific attentiveness. When the attentive awareness between the consciousness of the practitioner and his [/her] practice is unbroken, this is dhyāna.”

In II.48, “Patañjali says that the pairs of opposites do not exist in the correct performance of an āsana clearly [implying] the involvement of dhāraṇā and dhyāna.”

“As praṇava (sacred syllable Ōṁ) has three letters ā, u, ṁ, which stand for generation, continuation, and culmination in words or actions, āsana too has three movements. The first is going into position – akāra (the first letter of the praṇava). The second is establishing and staying in the āsana – ukāra (the second letter of the praṇava). The third is coming out of the position – makāra (the third letter of the praṇava). In this way, an āsana mentally expresses the praṇava mantra of āuṁ, without uttering it. If a practitioner with a clear intention retains the significance of āuṁ and practices the āsanas, observing the three syllables of āuṁ, [s/]he becomes involved silently in the awareness of āuṁ.”*

“This way of practice diffuses the flame of the seer so that it radiates throughout the body. The sādhakas then experience stability in the physical, physiological, psychological, mental, and intellectual bodies. In short, the seer abides and feels each and every cell with unbiased attention.”*

* Core of the Yoga Sūtras, by BKS Iyengar

** all other quotations from Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali, by BKS Iyengar

*** Sūtra translations from The Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali, by Prof. Edwin Bryant