The following are excerpts from Thus Spake BKS Iyengar by Noelle Perez-Christiaens,

©Institut de Yoga BKS Iyengar-Paris 1979

7. ĀTMAN

‘MERGING THE INDIVIDUAL SOUL (JIVĀTMAN)

WITH THE UNIVERSAL SOUL (PARAMĀTMAN)’

In many books dealing with Being one sees very knowledgeable distinctions between the Self and the self, the Self and myself, often rendered by the Latin ego. When someone speaks to you of ‘yourself,’ you know what s/he means. When someone speaks of the Self, you had so studied Einstein’s idea of Energy that it seemed to you there was nothing but It — all matter being, in the final analysis, energy — and that beyond the notion of person, of individual (of myself), there was a Source of Energy great and universal and neuter, as long as It was not manifested in some creation or other.

And as you realized that this energy Source is universal, that it underlies all creation, is the manifestation of everything, and precedes everything, at the same time you realized why Sanskrit — a language wherein the use of capital letters is unknown — doesn’t need to differentiate between the Self and the self. I remember being very perplexed when Iyengar said, “It’s the same;” those were the days before I discarded the notion of a personal God!

I was left with the problem of finding a translation for ātman, so often translated [as] ‘self.’ Mlle Esnoul came to my aid and suggested the translation ‘I’ or ‘me.’

We can say, then, that the fusion of the ātman in the Ātman is that of ‘me’ in the Being, an experience so dumbfounding, so inexpressible, of annihilation.

Doesn’t Iyengar say, over and over again that, “‘myself’ and ‘the self’ are one and the same?” In 1959 he wrote me, “When the mind is no longer a screen, the Soul (Ātman, the Being) is free and it shines as pure as crystal with no reflection on it. As the self is free from contact of things, that is the state of experiencing Samādhi.” (A45) I first used the French word ‘âme’ to translate ātman, which Iyengar expressed [as] ‘self’ or ‘soul.’ But after my experience of 1977, I see perfectly well that they might all be rendered by ‘BEING.’ Indeed, at the instant when thought is stopped by the energizing capture, an immense silence installs itself in one, and the BEING is revealed. No ’whys’ or ‘hows’ of a relative nature from the level of duality come to disturb the fact of being without qualification or modality: BEING is all.

In 1963 Iyengar added, “When the mind is controlled, what remains? The soul. That is the very purpose of yoga.” (F25) In 1968 another lexical difficulty was clarified: “…the consciousness of the heart, where the true Self reveals itself.” (J59) In Sanskrit, ‘heart’ is Hṛdaya (or Hridaya); not the organ, but what we mean when we say, ‘the heart of the matter,’ ‘the heartland of the continent,’ ‘the heart of the forest;’ that is, the deepest, central part of a being, the source of life. It is indeed in the depths of a being, well below all surface impressions, that the BEING reveals itself, annihilates all, dissolves all, absorbs all in Itself.

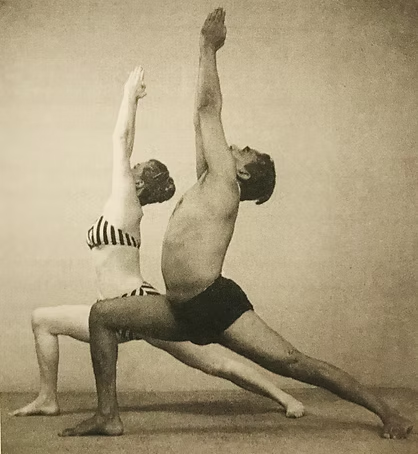

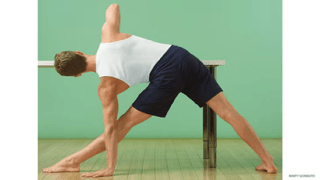

But for us this cannot come to pass outside of life, that is outside of āsanas, which are like rough maps. Iyengar specifies, “As long as you do not live totally in the body you do not live totally in the Self. Total awareness.” (X177) Here we could transcribe all his instructions on skin, on sensations; we might not betray him saying, ‘my body, my dear guru’ or ‘the body must silence the intellect and put its feet firmly back on the ground!’ If the attention on what is happening inside is not substantiated and continuous, the danger of fragmentation is ever-present, and the intellectual brain thrashes about, keeping the individual on the surface of her/himself. The sentient, animal brain can put wo/man back where s/he belongs and give her/his intelligence – and not her/his intellect – the chance to think calmly. Only the experience of reality can help a being to regain her/his balance and approach the consciousness of HER/HIMSELF: the BEING the s/he is.

An āsana is a slice of life slowed down, a rough map which allows for observation and correction; thus the Master specifies: “The āsana is an enquiry: who am I? Throwing out the parts until only the self is left. The final pose is ‘I am’.” (X181)

How many years must one work, in order to finally succeed in putting the profound truth of such a sentence to the test? Yet those who have really let themselves be caught up, who are beyond basics, and who are willing to give up everything in order to let yoga perform its work of merciless ‘peeling,’ can probably begin to render thanks to Iyengar for the profound wisdom which dictated to her/him such a sentence, uttered luminously out of uncommon experience of life!

* Cf. L’Aplomb, base de l’équilibre psychosomatique-N. Perz-Christiaens, Part V Ch 3

8. STHIRA AND SUKHA

“TATRA STHIRA-SUKHAM ĀSANAM”

A FIRM, STABLE SITTING POSTURE

(Patañjali II.45)

When the great Patañjali wrote [the] sūtras he collected, for the benefit of his followers, instructions from the great yogi of his time. We know that the sūtra designates a particular literary genre consisting of ‘stringing pearls on a thread’ (sūtra); it’s a rosary of mnemonic texts for teaching. Thus we won’t find plentiful explanations for beginners in the sūtras; rather a succinct resumé useful to the experienced pupil who can read ‘between’ the lines.

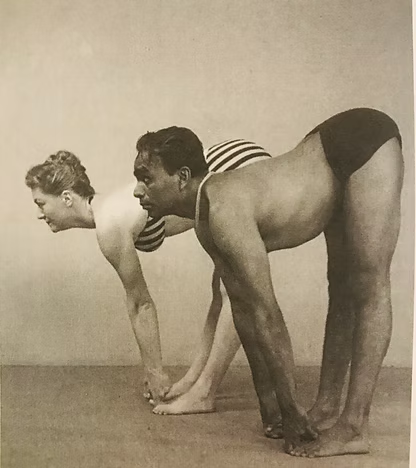

Now Patañjali says that the correct seat or foundation for meditation must be sthira and sukham. As we have seen for samasthithi*, sthira comes from the root STHA, which also gives the adjective ‘stable.’ Sukham is an adjective signifying the comfort of a wheel whose hub is well-centered. It’s a word right out of the experience of the nomadic peoples – Indians of today – who travel in ox-carts along bumpy country roads.

These two adjectives are thus extremely important for us, not only in the case of the posture for meditation, which does indeed require a very good seat, but also in that of any other posture, sitting or standing. In all postures the foundation is of prime importance. For the practice of yoga will lead us little by little towards samādhi along the bumpy roads of our lives.

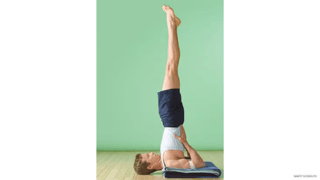

How does Iyengar translate these basic requirements for a good seat, in order to bring them within our reach? “In mediation, the mind is still but razor-sharp, silent but vibrant with energy. This state cannot be achieved without a firm, stable, sitting posture, where the spine ascends and the mind descends, and dissolves in the consciousness of heart (Hṛdaya, the centre), where the true Self reveals itself.” (J59) When the foundation is comfortable enough for the spine to be effortlessly erect, then concentration can descend to be absorbed, dissolved, in the Being.

Several years later [BKS] returned to the same idea, “When you sit, first stability, then firmness.” (Q46) It’s of primary importance to note that the Master is addressing himself to Westerners, so often sprawled in seats they think are comfortable: for he has avoided the original notion of ‘comfort’ (sukham) which would be falsely interpreted by us and replaced it with ‘firm,’ an important word for the choice of a seat. Indeed, so that the spine may surrender absolutely to Gravity, comfort demands that the seat be firm and soft: firm at the base and soft under the skin. Then the foundation is perfect if the correct height has been found. From all the sit is evident that nothing can be done on a poor seat, maladapted to that which is being practiced (duke, uncomfortable).

Other sayings come to perfect this new enlightenment: “It is the job of the spine to keep the brain alert and in position” (J64); this is true of any posture. A spine out of plumb results in compensations in the vertebra, the incorrect positioning of the skull, and ultimately a brain out of plumb. Then the brain anesthetizes itself, shuts itself off from discomfort, and a Westerner can live without suffering too much, but also without evolving towards the goal s/he took on when s/he began to practice yoga! In a lesson Iyengar explicitly said, “I showed you the tension on my face in that concentration, remember? This is that tension known as rigid stillness. The rigid stillness is not a state of silence. The rigidity is a vibration.” (Q56) It is patently true, when a stable, comfortable seat has finally been experienced, that there could not be the slightest rigidity or the slightest tension. As soon as I hold up my back, or activate the muscles of the back, my spine will conform to the idea I am imposing upon it; but it will immediately lose all mobility, all adaptability, to the slightest prompting of the Breath which comes from a total surrender to gravity. As soon as one holds, one becomes rigid, and as Iyengar says elsewhere, “rigidity is a form of egotism,” a return to oneself, an expression of deeply felt infantile pleasure of the active ego!

Along this road to meditation, towards the complete dissolution of everything that makes me see myself as a person opposed to the Being, the comfortable foundation in gravity permitting absolute mobility is the basis for absolute immobility. This may seem incompressible to beginners. By ‘absolute immobility’ I mean not that which we think we are producing, which is rigidity, but that stability given by a complete non-resistance to gravity. It is in the perfect silence of all manifestations of my ego that finally the Being is manifested, the Being that I am without having realized it.

Patañjali frequently opposes sukha (su-kha, the good hub), comfort, ease, wellbeing; and dukha (du-kha, the uncomfortable hub), lack of ease, discomfort. Sukha alone is the true way. -(Patañjali II.7-8, and 46).

*Cf., L’Aplomb, base de l’equilibre psychosomatique, N. Perez-Christiaens, Part V, Ch 3