The following are excerpts from Thus Spake BKS Iyengar by Noelle Perez-Christiaens, ©Institut de Yoga BKS Iyengar-Paris 1979

1. RASA

“YOU HAVE TO SAVOUR THE FRAGRANCE OF A POSTURE”

‘Fragrance’ is a sensory word—how can a posture have fragrance? This word expresses an agreeable sensation — how can an insufferably difficult posture produce an agreeable sensation? In this simple little word many have a chance to see that they are on the wrong track as they work to the breaking point with so much love and goodwill!

I discovered that the Sanskrit word Iyengar is translating is rasa (Patañjali, II.9). Rasa comes from the root RAS: to taste, to relish a taste; rasajña is one who savours, knows enjoyment; rasajñatva means poetic taste; rasayoga (in the plural) is a harmonious group of flavours.

Rasa is a sort of magnetic current flowing from the artist to her/his circle of auditors and back again, charged with the artistic emotion s/he created in them. It’s a tenuous, vibrating whole through which the spirit passes and transforms an ordinary Indian and makes her/ him thrill to eternal Vibration. It is el duende, which makes the matador sublime and enraptures the enthusiastic plaza, making the people rock in vibrations too powerful for simple mortals, unless they have been hoisted to that level. All this is rasa.

Is this what one experiences when toiling over ‘our’ postures or when one proudly performs fifty or a hundred backbends at a go? No. We are clearly on the wrong track: go seek elsewhere that which the Master would like to bring us to savour with him! Careful, though: Indians are excellent merchants, all Easterners are more cunning than we are, and if we are looking for something other than true fragrance, we will end by getting what we seek. Iyengar has said this clearly: “In ancient times, pupils went in search of gurus. Now gurus go in search of pupils. The is why spirituality has lost its fragrance.” (J81)

Here is a serious warning! From time to time, [we must] step back and ask ourselves sincerely what is it we are looking for, and if, we haven’t foundered in an easy, superficial, and highly physical yoga: whether we taste the rasa or not will give us our answer.

2. BRAHMĀSŪTRA

“WATCH YOUR MEDIAN LINE”

Several ideas, which Iyengar describes differently, all express the same sensation, and seem all to be included in what treatises of Indian dance and sculpture call Brahmāsūtra, the thread of Brahmā. Among the sensations which Iyengar tries to make us feel are the axis, parallelism or symmetry, and the ‘median line’. Perhaps there are others: these three seem to me to be the essential ones.

As we will deal with the axis later, I will only allude to it here. However, I will try to define the sensation of the thread of Brahmā, of symmetry of the two sides of the body, or the parallel work of each side along the median line [an anatomical line created at the juncture of the medial or saggital, and frontal or coronal planes]. I believe that it does seem as though this is what Iyengar is saying several different ways.

In ancient India, no artist could begin work without having had a solid preparation in yoga, including āsana, prāṇāyāma, and [dhyāna] meditation. [S/]He therefore had to have practiced a balanced posture in a seated position, without which no cosmic reintegration is possible. It is evident, then, that the notion of ‘thread of Brahmā‘ or ‘plumb-line’ is well placed in the sūtras concerned with the dance and the proportions of statutes.

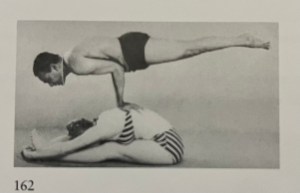

The different yoga postures are for us more and more subtle forms of balancing, or more and more refined foundations for concentration. As Iyengar says so well, they are application of an art in which the body is the material to model for the stone to chisel according to the idea the artist wishes to express. In sum, we are the stone, the sculptor is Brahmā, and the technique used is yoga. When we say ‘Brahmā‘ we might as well say: Harmony, Air, Silence, Peace, or Gravity. All of these are tangible manifestations of the non-manifested Energy, which remains quite esoteric a notion as long as It has not caught us up in Itself.

Among these tangible manifestations of Creative Energy, certain [ones] are fruits, like Harmony and Silence; others are rather agents like Air and Gravity. Without Gravity, the Air could not balance anything on the earth.

In the article The Dance and Sculpture in Classical Indian Art,* Kapila Malik Vātsyāyan writes, “Vertically, the human figure is conceived as composed of two halves, one on each side of the median line, the Brahmāsūtra, a fixed and invariable line representing the immutable force of gravity.” In a flash, we have here two notions Iyengar dwells upon: on the one hand, the axis of gravity every being must submit to, or live under pain of sprains and inflammations, in a state of constant aggression against the Cosmos – speaking of ahimsa (non-violence) but living in a state of himsa (aggression, injury); and on the other hand, the median line of the human body. Our task is always to bring the later to coincide with the former. How does the Master attempt to make us understand this median line? “The crown of the head, the centre of the forehead, the root of the nose, the tip of the nose, the middle of the sternum, all should be on the line.” (Q40) How could he be more explicit? We can well understand why he recommends to us, “always watch your median line.” (L2)

We find an echo of this in Vātsyāyan, “All movements are visualized in relation to the vertical median.” Several lines later, we read, “In Indian sculpture the study of flexion or bhañgā is essentially the study of the distribution of masses and the codification of the laws of balance.” We should not be surprised when Iyengar explains that our efforts of passivity and activity, “must test and ‘weigh’ the masses of the body on each side, as one estimates the weight of a piece of fruit in the hand.” He adds that this work of passivity and activity must balance weight evenly on each side of the body, “should weigh evenly on both the left and the right sides. Only then will lightness come.” (X322) Once all the weight has been brought gently back on to the median line and entrusted the thread of Brahmā, to Gravity, what could be left weighing heavily against it? Obviously, this work demands an enormous degree of attention. It’s a slow road but a sure one, towards great lightness — and freedom.

Iyengar explains this thought in other terms, “The right and left have to meet in the centre.”(Q40) Consider the force conveyed by the word ‘meet’, as in the expression ‘to meet one’s death.’

Returning to Vātsyāyan, we find: “We call samabhañgā a position which is perfectly balanced: the two halves of the body, one on each side of the Brahmasūtra, are of equal weight and the distribution of the total weight is perfect. The physical balance produces a spiral and emotional balance. This is why gods and goddesses, and also humans in a state of peace (śanti), stillness, and collected thought are shown in samabhañga.” She adds that “all the sattvika pictures of Indian sculpture are shown in this attitude.“

Iyengar continues: “that (meeting in the centre) means you are completely in contact; if there is looseness, there is no contact at all: the self and the body have lost the contact, so you learn nothing.” (Q40)

We could also quote many other sayings of the Master on the frantic search for balance, the gift of Brahmā the creator, which must not be held by the muscles but by the spirit, but we will content ourselves with one: “You have to work to obtain a perfect balance between both sides of the body” (K14) — here is the Brahmāsūtra again!

Echoing this union, Iyengar evokes, which arises out of the balance in Gravity, Vātsyāyan writes from a balanced creation in sculpture or dance (and we would add yoga) emanates “an aesthetic joy close to that supreme happiness that results from the union of the soul with God.” I believe his translator thought this was the best image to express the idea of the union of the ātman in the Ātman, or as Iyengar says, “the union of the Jivātman in the Parāmātman,” as we will see later on.

This work of constantly relinquishing one’s weight to gravity, to live on the thread of Brahmā and not to leave it, brings one gradually to taste rāsa. Rāsa will carry the true seeker on to ĀNANDA (Bliss).

*in Diogene, 1964, 45-48, pp 25-38

A last sentence from Vātsyāyan gives us a glimpse of the secrets of Indian mystical doctrine, which Iyengar does his utmost to transmit to us: “The position of samabhanga to which the dancer (of bharatanatyam) returns is of primary importance in Indian choreography, and , with rare exceptions, corresponds to a posture expressing the serenity of perfect balance.” She adds, “It is a position in which the weight is equally distributed between the two halves of the body.”

Bit by bit, we see the intricacy of the ideas: the centre and the two sides, the plumb-line, the thread of Brahmā, the perfect balance in the total surrender of one’s weight to Gravity. All these notions form a background against which one seems to see Iyengar as if in filagree. Two concise terms from Sanskrit appear to have produced this, Brahmāsūtra and Sama. We turn next to sama.