by Julie Gudmestad, Yoga Journal, July/August 2001

Practiced with careful alignment, yoga poses can help alleviate past neck problems and prevent future ones.

JUDGING FROM THE COMPLAINTS OF my physical therapy clients, chronic neck tension is a modern American epidemic. Even the more benign consequences – the painful crick in your neck, the dull headache radiating from the back of your skull – can be mighty annoying. The more serious ones, like pinched nerves, arthritis, and damaged discs, can be debilitating.

Fortunately, yoga can do wonders for neck problems while simultaneously teaching safer, healthier posture habits. But some of the poses that can help you, like Śīrṣāsana (Headstand) and Sarvāṅgāsana (Shoulderstand), can also do harm if performed incorrectly. It’s important to approach them with knowledge of proper alignment.

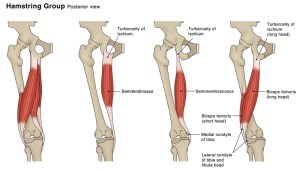

Let’s take a look at the muscles of the back of the neck. Why do they cause so much trouble, and how can we use yoga to help them function better? The primary muscles of the back of the neck are the levator scapulae [above], which extend from the cervical (neck) vertebrae to each inner upper scapula (shoulder blade). Lying on top of the levators and also inserting on the shoulder blades are the upper trapezius muscles [below- orange], which originate on the base of the skull and the neck vertebrae. Together, these muscles lift the scapula and backbend the neck. The levators and trapezius muscles also help to turn the head and sidebend the neck.

The stress of a busy lifestyle with deadlines, difficult people, and lack of sleep certainly tightens neck and jaw muscles. A forward head posture is also a factor for many people. An average head weighs 12 to 15 pounds, when that weight sits forward of the central line of the spine, the muscles on the back of the neck have to work very hard to hold the head up against the pull of gravity.

Whether due to stress or poor head-neck alignment, chronic tightness in the levator scapulae and the upper trapezius can lead to significant neck pain. As the muscles pull down on the base of the skull and upper neck, they also pull up on the scapula. All this adds up to compression on the cervical vertebra. Such tightness and compression can lead to arthritis, cause nerve pressure that makes pain radiate down the arm, and increase the likelihood of neck muscle injuries.

Do no harm

JUST AS IN MEDICINE, a key rule in haṭha yoga is “First, do no harm.” It’s crucial to avoid common yoga mistakes that can result in neck injury. If you come to yoga after years of neck tension, the muscles at the back of your neck will probably be quite short and tight, limiting your ability to bring your head toward your chest. Since you need a great deal of this neck flexion to do Shoulderstand, forcing a tight neck into the pose can strain the muscles and ligaments. Even worse, forced flexion can cause cervical vertebrae discs to bulge or herniated, serious injuries that may take many months to heal.

Many people habitually tighten their neck and shoulder muscles when they concentrate, and it’s easy to carry that habit over into yoga. This can be especially true in backbends. Students tend to overcontract the neck, sticking the chin out and up and compressing the back of the neck. This action can result in an unpleasant headache after backbends such as Bhujāngāsana (Cobra), Śalabhāsana (Locust), and Ūrdhva dhanurāsana (Upward-facing bow).

Fortunately, one backbend actually lengthens the back of the neck. Doing Setubandha (Bridge pose) supported on bolsters for a few minutes three or four times a week can help prepare you for Shoulderstand.

Decompress your neck

IT’S HELPFUL TO LEARN HOW TO relax, lengthen, and decompress your neck before you try to do it in a pose. Here’s a simple exercise to prepare you for keeping your shoulders down and neck relaxed in yoga poses. Hold an object weighing one to two pounds in each hand, letting the weight of the objects pull the shoulder blades down. Make sure that you keep the breastbone lifting up so that the tops of the shoulders don’t pull down and forward, collapsing the chest. Now set the objects down and see if you can find the muscles you need to pull your shoulder blades down just as the weights did.

These muscles are called the lower trapezius [second skeleton- plumb] . They attach to the vertebrae of the midback and insert on the inner border of the shoulder blades. They are the antagonist muscles to the upper trapezius (traps)– in other words, they perform the opposite action – and are very important posture muscles, helping support the spine in the midback. Unfortunately, when the lower traps are too weak to counteract the pull of the stronger and tighter upper traps, the scapulae will tend to ride up, compressing your neck.

Now let’s take these lessons and apply them in an āsana. Stand with your legs ready for Vīrabhadrāsana II (Warrior II). Lift your breastbone up and pull the scapula down: This action requires release and lengthening in the upper traps and contraction and firmness in the lower traps. Next, lift your arms out to the sides to shoulder height, turning your palms up. Feel how turning the palms up helps bring the shoulders down and activates the lower traps. Keeping that action and position of the shoulder blades, turn the palms back down; you now have the correct shoulder and arm position for Warrior II and many of the other standing poses.

It is also important to incorporate this action into Headstand, so that you can protect your neck from compression. When you’re upside down, gravity pulls the shoulders toward the ears, so you need extra awareness and strength in the lower traps. While in Headstand, have a helper put a finger on each shoulder blade at the base of the neck and gently draw the fingers away from the floor, lifting your scapulae toward your hips. At first you may get disoriented while upside down, but once you’ve felt the proper direction of lift, you should find it easier to engage your lower traps.

Before you begin working on Headstand, you should probably spend at least several months working on a variety of other poses to strengthen your back and neck muscles and improve the alignment of your spine. It’s also a good idea to be strong in all of the arm and shoulder muscles before trying Headstand. The small cervical vertebrae are designed to support only the weight of the head, but when we do Headstand, they are supporting nearly the full weight of your body. Unless you have developed enough strength in the arm and shoulder muscles to take a little of the weight off your head and to balance the body if is shifts around slightly in Headstand, you can injure your neck. Work often on Adhomukha śvānāsana (Downward-facing dog) and Handstand to build the strength and endurance that will help prepare you for a safer Headstand.

One final thought about Headstand: A normally curved neck will bear the weight of Headstand much more easily and safely than an overly curved or overly flattened neck. To check your own neck curve, stand in front of a mirror. With a normal curve, your chin should be level and you should be looking into your own eyes in the mirror. Put several fingers of one hand across the back of the neck. The tissues there should feel soft, and the neck should curve slightly forward. Now drop your chin and feel how the tissues become hard and the curve flattens. Then lift the chin and feel how the back of the neck compresses. In Headstand, if your head contacts the floor toward the forehead, your neck curve increases and the back of the neck compresses. If your contact point is toward the back of the head, your neck flattens. When you do Headstand, make sure you are centered on the very middle of your head. Look in a mirror while you’re in Headstand – or have a teacher look at you – and make sure that your eyes look straight ahead, your neck curve is normal, and the back of your neck is soft.

Practicing yoga poses with conscious awareness of your head, neck, and shoulder alignment will help you gradually break the habit of chronic neck tension. The benefits to your health and well-being will be many – and you probably won’t be seeking an appointment with me for a yoga-related neck injury.