Or Diminished Range of Motion

A few years ago my nephew approached me at a family get-together, inquiring what he could do to relieve tension in his shoulders. As it turns out my own experience five years earlier involved similar discomfort. Later, this was compounded by diminished range of motion (‘frozen’) in one arm, and after ‘healing’ it the other began displaying equivalent diminishment. Placing the ‘stiff’ arm in the sleeve of a coat was always painful in the shoulder. Below is what I learned as a result.

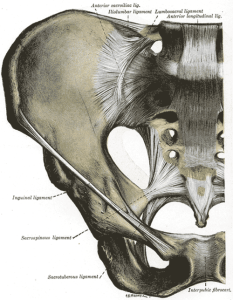

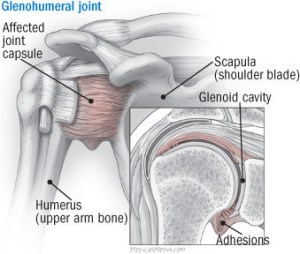

Adhesive capsulitis, commonly known as ‘frozen’ shoulder, is a painful condition, when the strong connective tissue surrounding the shoulder joint becomes thick, stiff, and inflamed. This joint contains ligaments that attach the top of the upper arm bone to your shoulder socket, firmly holding the ball and joint in place. It ‘freezes’ when discomfort makes use of the shoulder less likely. Lack of use thus causes the capsule to thicken and become tight, making it even more difficult to move. Often, sleeping on one’s sider further aggravates the condition.

Adhesive capsulitis, commonly known as ‘frozen’ shoulder, is a painful condition, when the strong connective tissue surrounding the shoulder joint becomes thick, stiff, and inflamed. This joint contains ligaments that attach the top of the upper arm bone to your shoulder socket, firmly holding the ball and joint in place. It ‘freezes’ when discomfort makes use of the shoulder less likely. Lack of use thus causes the capsule to thicken and become tight, making it even more difficult to move. Often, sleeping on one’s sider further aggravates the condition.

The NIH explains that “adhesive capsulitis is a painful and debilitating condition characterized by progressive stiffness and loss of both active and passive shoulder motion. This condition typically occurs in middle-aged individuals, with a higher prevalence in women. Adhesive capsulitis develops in 3 stages: the painful, the freezing, and the thawing phase. It can last for months to years. While the exact pathophysiology remains unclear, inflammation, fibrosis, and contracture of the shoulder joint capsule play a key role. Risk factors include diabetes, thyroid disorders, bursitis, tendonitis, prolonged immobilization, or previous shoulder injuries. Diagnosis is primarily clinical, with imaging used to rule out other causes of shoulder dysfunction. Management focuses on pain control, physical therapy, and in refractory cases, corticosteroid injections, or surgical interventions such as capsular release.”

Although the cause of this ‘freezing’ is not fully understood, there are several movement options which gradually return greater motion. I used these:

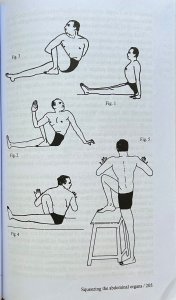

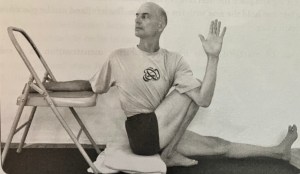

- Clasp the Wrist- Hold the wrist on the diminished side at the back. Relax into this hold, as best you can. Eventually, you’ll be able to switch.

- Hands in the Sink I- Facing away from the kitchen sink, place your hands inside it and gently step forward making sure to release the shoulders.

- Hands in the Sink II- Interlace you hands in the sink, then gently straighten elbows while releasing the shoulders back. Switch interlace. Eventually, you’ll be able to join the palms.

- Wrists in the Loop I- Using a strap loop over doorknobs, face away from the door edge. Place wrists inside loop ends, then straighten elbows, release shoulders, and gently step forward.

- Wrists in the Loop II- Cross the loop ends before inserting wrists. Now gently move forward.

- Arms Overhead- Take a strap loop (armpit to armpit in length) over the wrists in front, with thumbs in. Lower the shoulder blades and raise then lower arms, keeping elbows straight.

- Arms Overhead Variations- As above, but have thumbs up. Then try thumbs out.

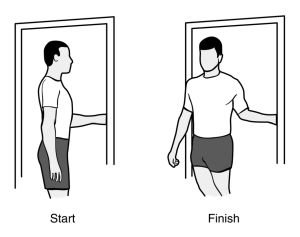

While researching the topic I found this stretch, which works very well:

- When facing the side of a door jamb, place palm beside the trim.

- Gently, walk to turn and face straight out.

- Hold for a few breaths. Return and repeat.

Harvard Health Publishing offers the following:

Always warm up your shoulder before performing your exercises. The best way to do that is to take a warm shower or bath for 10 to 15 minutes. You can also use a moist heating pad or damp towel heated in the microwave, but it may not be as effective.

In performing the following exercises, stretch to the point of tension but not pain.

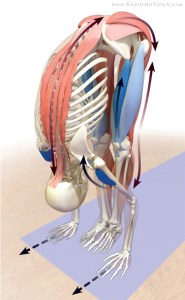

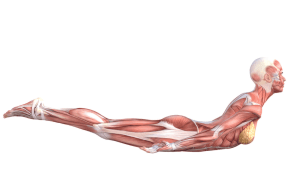

Pendulum stretch

(Perform this exercise first.)

- Relax your shoulders.

- Stand and lean over slightly, allowing your affected arm to hang down.

- Swing the arm in a small circle — about a foot in diameter.

- Perform 10 revolutions in each direction, once a day.

- As your symptoms improve, increase the diameter of your swing, but never force it.

- When you’re ready for more, increase the stretch by holding a light weight (three to five pounds) in the swinging arm.

Towel stretch

- Grasp a three-foot-long towel with both hands behind your back, and hold it in a horizontal position.

- Use your good arm to pull the affected arm upward to stretch it.

- You can also perform an advanced version of this exercise with the towel draped over your good shoulder.

- Grasp the bottom of the towel with the affected arm and pull it toward the lower back with the unaffected arm.

- Do this stretch 10 to 20 times a day.

Finger walk

- Face a wall three-quarters of an arm’s length away.

- Reach out and touch the wall at waist level with the fingertips of the affected arm.

- With your elbow slightly bent, slowly walk your fingers up the wall, spider-like, until you’ve raised your arm to shoulder level, or as far as you comfortably can. Your fingers should be doing the work, not your shoulder muscles.

- Slowly lower the arm (with the help of the good arm, if necessary) and repeat.

- Perform this exercise 10 to 20 times a day.

Cross-body reach

- Sit or stand.

- Use your good arm to lift your affected arm at the elbow, and bring it up and across your body, exerting gentle pressure to stretch the shoulder.

- Hold the stretch for 15 to 20 seconds.

- Do this stretch 10 to 20 times per day.

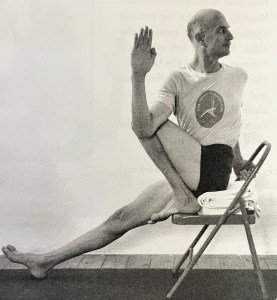

Armpit stretch

- Using your good arm, lift the affected arm onto a shelf about breast-high.

- Gently bend your knees, opening up the armpit.

- Deepen your knee bend slightly, gently stretching the armpit, and then straighten.

- With each knee bend, stretch a little further, but don’t force it.

- Do this stretch 10 to 20 times each day.

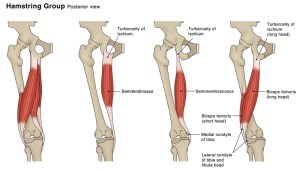

Strengthening the rotator cuff

After your range of motion improves, you can add rotator cuff–strengthening exercises. Be sure to warm up your shoulder and do your stretching exercises before you perform strengthening

Outward rotation

- Hold a rubber exercise band between your hands with your elbows at a 90-degree angle close to your sides.

- Rotate the lower part of the affected arm outward two or three inches and hold for five seconds.

- Repeat 10 to 15 times, once a day.

Inward rotation

- Stand next to a closed door, and hook one end of a rubber exercise band around the doorknob.

- Grasp the other end with the hand of the affected arm, holding the elbow at a 90-degree angle.

- Pull the band toward your body two or three inches and hold for five seconds.

- Repeat 10 to 15 times, once a day.