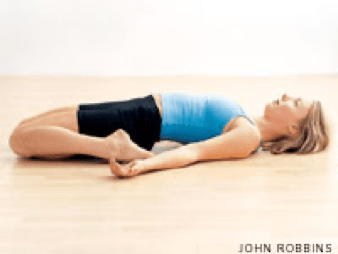

Don’t let tight quadriceps keep you from one of yoga’s most relaxing poses.

By Julie Gudmestad

Supta virāsana (Reclining Hero Pose) is a passive backbend and a wonderful chest opener that’s extremely relaxing and restorative. It’s the perfect antidote to an overstressed life—as long as your knees and lower back aren’t screaming in agony. Why do some students experience such pleasure and others pure pain in this pose?

It’s likely that it has to do with the length in the muscles of your front body. Supta virāsana is a classic front-opening pose. As you sit between your heels, it stretches the fronts of your ankles and lower legs. As you lie back, your quadriceps and abdominal muscles lengthen and open. Extending your arms overhead adds a shoulder and chest stretch. All in all, it’s a wonderful position for spacious, relaxed breathing.

But sometimes your lower body doesn’t cooperate. If you have knee and back pain in this pose, the culprit is often tightness in your quadriceps, specifically the rectus femoris (RF). I recommend working on this muscle if you’re having difficulties in Supta virāsana. One caveat, though: If you have persistent pain in your lower back or knees in the pose, consult your health care provider to rule out structural problems or injuries, then find an experienced teacher for guidance. If you’re uncomfortable doing the pose even with skilled supervision, substitute another supported backbend, like Supta baddha koṇāsana (Reclining Bound Angle Pose) or supported Setubandha sarvāṅgāsana (Bridge Pose).

The RF is one of the four muscles that form the quadriceps on the front of the thigh. It sits directly under the skin, running right down the center of the thigh between hip and knee. This muscle originates on the front pelvis above the hip socket, and then crosses the front of the hip to join the other three quads: the vastus lateralis, v. intermedius, and v. medialis. The three vastus muscles originate on the femur, and all four quadriceps converge into a common tendon, which attaches to the kneecap. This tendon then extends down past the knee, becoming the patellar ligament, which inserts on the shinbone. All four muscles contract to extend (straighten) the knee. Because RF crosses the hip, it also acts to flex (bend) the hip when the thigh and torso are pulled toward each other.

Long and Strong

The joint a muscle is connected to must oppose the lengthening action in order to stretch any muscle. In this case, because the quads extend the knee when they contract, you must flex the knee to lengthen and stretch them. And since RF is connected to two joint muscles, you have to position both joints properly to fully lengthen it. That means you’ll have to simultaneously flex (bend) the knee and extend the hip (bring the thighbone in line with or behind the torso). This position describes Supta virāsana perfectly: When you sit between your heels, your knees are deeply flexed, and when you lay your torso back on the floor, your hips are fully extended.

The trouble usually arises when RF doesn’t lengthen enough to allow the knees and hips their full range of motion. Often the muscle is too short and hasn’t been stretched enough. Perhaps it’s been worked hard or you’ve spent long periods sitting in a chair with hips and knees both at 90-degree angles. And if you’re like most yoga practitioners, you probably spend much more time stretching the backs of your thighs than the fronts. In any case, if all four quadriceps are short and tight, they will prevent the knee from flexing fully, and you will have trouble lowering your hips toward your heels— never mind sitting between them.

Trying to force your pelvis down between your heels before the quads are long enough is counterproductive and painful, and can injure your knees. Instead, sit in Virāsana on a block or other firm prop for a few minutes each day, and all four parts of the quads will gradually stretch out. Over time, you’ll be able to reduce the size of your prop until eventually you’ll be able to sit comfortably on the floor between your heels.

To further protect your knees, make sure your feet and toes point straight back behind you and not out to the sides. Also, while you’re kneeling before you sit, dig the fingertips of each hand deep into the back of the knee, pull and hold the flesh of the calf straight back toward the heel, and then move your fingers out as you sit down. Some people find it helpful to gently pull the calf flesh slightly out toward the little-toe side as they pull it back. This rearranging of the calf seems to open a little more space inside the knee and helps avoid undue twisting of the joint.

A tight RF can also cause problems for the lower back by limiting full extension at the hips. If your RF is tight and short, even sitting down on a block near your heels takes up any slack the muscle has to offer. As you move to lie back, the muscle can’t lengthen any more, and your pelvis will be stuck in a forward tilt. That places your lower back in an exaggerated and uncomfortable arch. Worse still, if one RF is shorter than the other, just one side of the pelvis will tilt forward, causing the pelvis to twist in relation to the spine and knees. This can strain the knees, sacroiliac joints, and lower back.

Body Balance

A good solution is to balance your stretching between the fronts and backs of your legs. If you’re the proud owner of tight, short RF muscles, be sure to stretch them just as frequently as you do your hamstrings. You’ll stretch the RF most effectively if you work on one side at a time, because the muscle is tough (containing lots of gristly connective tissue) and potentially strong. When you try to stretch the left and right together in poses like Supta virāsana, or Bhekāsana (Frog Pose), they will—like two mischievous kids—simply overpower the stretch, causing your back to overarch.

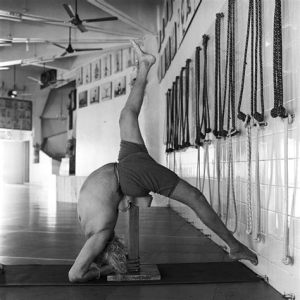

To get an effective RF stretch, you’ll need to flex the knee while you extend the hip in a position you can hold for one to two minutes. Ardha bhekāsana (Half Frog Pose) is a good way to stretch the RFs one at a time. Lie face-down with your shoulders in line with your hips and your knees three to four inches apart, bend your right knee and lift your right foot toward your buttocks. Use your hand or a strap to catch your foot, and before you pull on the foot, press your pubic bone into the floor, eliminating any gap between the front of your hip and the floor. Then, maintaining the three- to four- inch spread between your knees, gradually pull your heel toward the outer edge of your buttock (not the tailbone). Repeat on the other side. Remember, don’t force: Pain in your knee or lower back is never a good thing, and muscle pain can cause the muscle to contract and resist the stretch.

You can also work on your RF muscles at a wall. Start on your hands and knees facing away from the wall, with your feet touching it. Place one shin on the wall, perpendicular to the floor, foot pointing up, and the knee within two to three inches of the wall with plenty of padding beneath it. Now bring the other foot forward to stand flat on the floor a couple of feet from the wall, and you’ll be in a modified lunge.

Next, put your hands on two yoga blocks or a chair seat to support yourself as you gradually move your tailbone down and away from the wall and into a deeper lunge. As the RF stretches and gradually lengthens, gently and slowly lift the hips, chest, and torso back toward the wall. If your lower back starts to hurt, ease off.

As you work over the weeks and months to lengthen the fronts of your thighs, come back to Supta virāsana from time to time to see whether you’re ready to practice it comfortably. You may find that it helps to start with a bolster or stack of folded blankets under your back and head. In the meantime, you’ll have an opportunity to bring yoga philosophy to life: By practicing patience and compassion, you’ll learn to breathe and relax into resistance and to persist in the face of a challenge that can’t be instantly resolved.

Julie Gudmestad is an Iyengar Yoga teacher and physical therapist in Portland, Oregon. She cannot respond to requests for personal health advice. Return to http://www.yogajournal.com/practice/2607/