By Jenny Snick (Yoga Journal Sep./Oct. 1983)

The sun streams in through the beveled glass window, creating bright patterns across Oriental and hardwood floors. Surrounded by exquisite Japanese vases, prints an scrolls, I wait for Mary Dunn, teacher and co-owner of the B.K.S. Iyengar [method of] Yoga Center in San Diego, to bring me tea. As she walks into the room, her warmth and liveliness fill the silence. At 40, she looks like a woman who is living to her potential. Her thick brown hair is cut short, and her skin is brown from the sun. Her strong and compact body is graceful, and the flexibility she has achieved in ten yers of yoga practice is evident in her every movement.

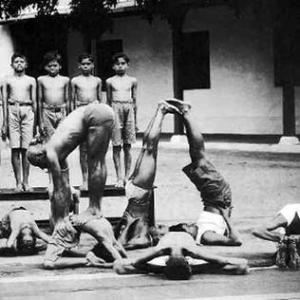

Mary was introduced to yoga by her mother, Mary Palmer, who lives and teaches in Ann Arbor, MI, and who studied extensively with B.K.S. Iyengar in India and England. It was Mary Palmer who helped convince Iyengar to come to the United States for the first time [*] in 1973. In 1974, when he was planning to return to the U.S., Rama Jyoti Vernon asked Mary Palmer to see if he would extend his visit to the West Coast.

Mary Dunn was then a beginning student of Rama’s, and living in Berkeley with her husband, Roger, and their two daughters, Louise, now 13, and Elizabeth, now 9. She attended Iyengar’s classes as a complete beginner. In fact, he used her as a model to demonstrate how to teach his method of yoga. “I knew my life would never be the same again after that first marathon class with him.”

Mary drew on the love of movement that had made her an accomplished figure skater and swimmer while growing up in Ann Arbor. She was eager to free her joints and muscles as Iyengar had shown her, and practiced diligently on her own, in class, and directly with Iyengar in the U.S. and India. She began teaching by substituting for Rama, and went on to teach at the Institute for Yoga Teacher Education in San Francisco (now the Iyengar [method of] Yoga Institute).

After 11 years in the Bay Area, Mary and her family relocated to San Diego, where they have lived ever since. Their home is decorated with Roger’s art collection and Mary’s family heirlooms, including and ebony grand piano. Mary, well-trained in music, now works daily with daughter Elizabeth, a talented pianist who attends the School for Creative and Performing Arts in San Diego.

The day begins early for the Dunns. Everyone rises at 5:30 a.m., breakfasts are eaten, lunches prepared, school books gathered, and all are on their way by 7:00. After Mary drops Elizabeth at the school bus, she continues to the B.K.S. Yoga Center, which she has shared with two women of the past three years. It is there, in a studio filled with props of all kinds, that Mary does the majority of her teaching. She also travels as a frequent guest of yoga centers around the U.S. and Canada.

As we begin our talk, Elizabeth comes in from school. Mary greets her, and together they plan the afternoon’s piano practice. As Elizabeth rushes up the stairs, Mary turns her attention to my questions.

JS: Mary, your classes seem inspired. Where does this inspiration come from?

MD: It comes from all aspects of my life. For example, while I was teaching trikoṇāsana, I looked out over the beginning class and they reminded me of my children when they were learning to dive off the side of a pool. When children dive, they don’t extend. They just stand on the side of the pool and fall in, head first.

There’s no sense of timelessness, of time stopping, which is what you want to see in a dive. I took that premise as a starting point for the class. I related how trikoṇāsana must not be like a belly flop where you’re just falling into the “pool”. You have to feel it as a swan dive. You go into the pose, extending indefinitely. In yoga we have an advantage because we can keep extending. We don’t have gravity forcing us to finish a pose. We can keep diving forever. All the standing poses are related to this feeling of always lifting, of expressing timelessness.

JS: Mr. Iyengar talks about the concept of time in the physical body. How does that fit with this idea of timelessness?

MD: Mr. Iyengar uses the front of the body to talk about the future, and the back to talk about the past and the need to always balance these. This balance gives a sense of timelessness. The physical experience of being in the present. When the awareness is complete and the mind still, the sense is one of meditation.

Meditation is being present, the ever-continuing present. Mr. Iyengar’s genius is taking psychological states and translating them into the physical arena where we can understand them. We might not know how to extend our consciousness yet, but we can learn to extend a finger and can learn from the physical analogy to start extending our consciousness. That’s why when you see his poses you can feel the expansions of his presence, and this is one of the things that makes his teaching so revolutionary.

The known and unknown body is another way he talks about the front and back body. The front is where our sense organs are located. As we look at ourselves in a mirror or at one another we hardly ever see what’s going on in the back body. We get to know our front and we don’t get to know our back, so the back is the physical analogy for the unknown body.

JS: As the knowledge moves into the back body, it seems we are depending less on our senses. Are we becoming more inward as we learn about the unknown?

MD: The concept of Pratyāhāra (withdrawal of the senses) does not mean that you don’t appreciate what is out in the world, but that you are not overwhelmed by that knowledge which comes through our senses. With yoga, you have some ability to get to know the world of the spirit, the inner self. That is the point of what we’re doing. All the different kinds of poses give us that knowledge in a different way.

That’s why it’s important to balance, not only do backbends without doing forward bends, or only sitting poses without doing standing ones, or all vigorous poses and no static ones. It’s important to have the whole balanced, because self-knowledge is different in active poses than in passive ones.

JS: Do you feel the process of yoga takes place only while practicing āsana?

MD: I have had an interesting experience a number of times with a posture I have been working on and am unable to do. I will dream about it and it has been so vivid that I have awakened with memories of the dream, and will be able to get out of bed and do the pose. I know that the process goes on all the time, and the solutions appear, not by trying so hard, but by allowing the experience to develop within the whole person, not just the intellectual function or the physical side, but the whole person.

The pose is the outward manifestation of the integration that has taken place. This is how Mr. Iyengar’s method works. It accounts for many different planes of reality. It is not as if someone has thought up and superimposed a system upon human’s mind, body, and spirit. Instead, it is a revelation of what’s already there.

JS: You believe there is a basic truth in the way the body should move, and as we learn how the hips should roll or the shoulders should open, for example, we have a deeper discovery and awareness.

MD: Yes , that’s accurate.

JS: Is it possible to become misguided in those movements, and is that how injuries occur?

MD: Definitely. You are misguided when you’re not listening sensitively to what’s going on in your body. For example, if a person works aggressively Hanumanāsana [**], the vulnerable hamstring muscles can be easily torn. Thus, the person must be willing to go quite slowly to allow the body to open without injury.

JS: The danger seems to come when the goal is more important than the process.

MD: Yes. That gets to the essence of it. If you are striving for a goal, you are in the future, and the goal is more important than what is going on in the present. It becomes a striving attitude.

JS: Obviously then, one of the teacher’s roles is to keep students from injuring themselves. What else do you feel a teacher does?

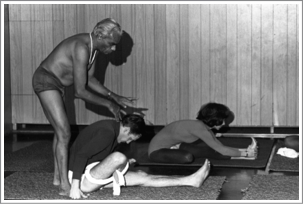

MD: A good teacher inspires by actually giving his or her own energy to the students so they have a sense of their own possibilities. What I teach comes from my own practice and from what I observe. I notice when the teaching is coming well, it flows so beautifully that I feel I am almost transported. I am absolutely beyond myself and in clear touch with what I’m seeing from my students. There is an accumulation of knowledge that I draw on, and I say things that I have not prepared in advance at all.

In contrast, as a more immature teacher I thought of myself, how the class was responding to me, how my demonstrations looked. Now I can get, beyond myself, and to the students more easily. I often feel Mr. Iyengar is right there in the room with me.

JS: Your class design is not from a set curriculum then, but from the needs of the students in the class?

MD: I absolutely believe that you select what you teach according to your students. If I don’t adjust the poses to fit the needs of the students, then I’m missing part of my calling. Yoga is not just the intricacy and stability we teach in standing poses. It is the fun and freedom of jumping, it is the serenity of inverted poses, it is the excitement of backbends and the softness and surrender of forward bends, the operation of twists. A teacher must bring all these things to the students at the appropriate time.

JS: And the richness of yoga is also expressed in this variety . . .

MD: It’s the most fantastically rich subject. This is what drew me so strongly to Mr. Iyengar during those first classes. I had the experience of being in the presence of a master and transcending myself in a way I had never done before. It was an unbelievable event for me and I haven’t been the same since. It set me on a path in which I continue to find more all the time. Often people ask me if I have ever tried t’ai-chi ch’üan or other arts of self-development, and my answer is no. Not because I have any feelings that they are not also worthy arts, but I’m engaged in an art which is so wonderful to me., and I haven’t, in any way, completely explored it yet. I am going to, and am now following this path of yoga as far as I can go, as far as it will take me.

JS: How do you feel yoga has helped you in other aspects of your life?

MD: In yoga we try never to lose sight of what we’re doing. Sometimes in working in a pose we think what we’re doing is able to touch our head to our feet, for example, but that’s not really what we’re doing it for at all. We are practicing those philosophical truths that we think are important as yoga students, those truths that we read about in the Sūtras. Then joining starts to happen and this spills over into the rest of our lives.

JS: What about people who have excelled at a physically demanding sport such as gymnastics? They have reached a beautiful control in their movements. Are they, although unaware of the yogic philosophy, actually realizing some of the spiritual growth that accompanies the practice of yoga?

MD: I think so, because I feel when you pursue any art to its highest form it becomes internal. On the other hand, it is also possible to become skillful at the āsanas without having yoga touch their soul. Caught up in the outer drama of the pose, hence caught up in the ego. We first view the world through a prism of the ego. When we give up the ego, we experience the inner drama. We see people and situations for what they are, not what we think they are or want them to be. The path of giving up the ego uncovers the spirit.

JS: Do you think that then ego can hold us back from doing the poses?

MD: Yes, absolutely. I have a student who says, “I can’t do that” each time I ask her to do an arm balance. Her ego, or perception of herself, is telling her that she is not an able person. So I am always telling her she can do it, pushing her to reach her potential to discover that capable part of herself that is hidden by the ego. It’s my job as a teacher to keep saying, “Yes, you can.”

JS: Mary, you give so much to us as student , are there any times when your family feels left out?

MD: Well, of course my mother [***] is fantastically pleased that I’m so involved in yoga. And my father is very supportive of us both. Every time I have gone to India he has come to help my husband run the household and take care of our two daughters. One major reason I have been able to pursue yoga so wholeheartedly is that my husband, Roger, has been very supportive from the outset. It’s meant a lot of schedule juggling, a lot of flexibility. Louise and Elizabeth accept my involvement with good humor. In fact one of them came up with the nickname “Swami Mommy,” which stuck.

JS: How long do you think a student should continue studying with a teacher?

MD: As long as the student feels he or she is learning a great deal from the teacher, they should continue. Once again, that work does not replace what the student learns on his own.

JS: Just one more question, Mary. Is the idealized pose the correctly aligned pose?

MD: Yes, if you take the phrase “correctly aligned” in a philosophical sense. When this complete alignment takes place, the wavering is gone on all levels. It’s as if a vibrating string on a stringed instrument has come to a place of stillness. You sense that potential for sound, but the string has become absolutely aligned so the waverings are no longe there. That’s the perfect pose.

It doesn’t do me much good to talk with the beginner about the philosophical ramifications of the yoga practice if she or he doesn’t know that in Utthita trikoṇāsana the front foot turns in 30°, the other out 90°, and align the kneecap directly with the toes, and so forth.

Those are the physical laws of the movement. If I don’t teach those first, and instead rely on high-sounding ideas, I may have people doing postures that are physically harmful. Those unaligned poses certainly aren’t opening up pathways of the nervous system the way a correct pose would, or inducing a sense of quietness in the mind.

Great disservice is done to beginners, if care is not taken installing the basics of the pose. Once beginners have the idea of alignment, even if they’re not limber or don’t have familiarity with many different poses, disservice is done when the vastness of the subject and the implications of what they’re doing is not addressed.

Jenny Snick has worked, and studied, with Mary Dunn for the past three years in their studio, the B.K.S. Iyengar [method of] Yoga Center in San Diego.

* At the invitation of Standard Oil heiress Rebekah Harkness, he came to the United States in 1956. American interest in yoga was growing—indeed, Indian gurus were already active there—but Iyengar was repelled by the country’s materialism. “I saw Americans were interested in the three W’s—wealth, women, and wine,” he told O’Connor. “I was taken aback to see how the way of life here conflicted with my own country. I thought twice about coming back.” Iyengar lived for a time in Switzerland and did not return to the United States until the early 1970s.

Read more: https://www.notablebiographies.com/supp/Supplement-Fl-Ka/Iyengar-B-K-S.html#ixzz890fM3dtA

** “The goal is not to hold at any cost an āsana that is painful, or to try to achieve it prematurely. This is how I hurt myself as a young practitioner when my teacher demanded that I do the Hanuman āsana, which involves an extreme leg stretch, without proper training or preparation.”

Read more: B.K.S. Iyengar, Light on Life, 2005 Royale, p. 50

*** Then in 1969, some fifteen years after Menuhin had first invited Iyengar to London, Menuhin gave a concert in Ann Arbor, Michigan, the home of Mary Palmer. Before her own first teacher in yoga had left Michigan, she had recommended ‘Light On Yoga’ to Palmer, saying “You have the finest book on the subject. Use it”. Her husband, a Professor of Economics in the University of Michigan, was due to take a sabbatical in India. Noting Palmer’s interest in yoga, Menuhin said to her “you must meet my yoga teacher in India. His name is BKS Iyengar”. Inspired both by Menuhin and this coincidence, she determined to meet Iyengar. Once she had reached New Delhi, she wrote to Iyengar and was able to go to Pune and study with him for three weeks. She also travelled to London to study with him at his ILEA classes.

Read more: https://www.kofibusia.com/iyengarbiography/biography.php

Thank you so much Gregor Maehle for your beautiful, honest, insightful and heartfelt response to my interview. Please don’t feel bad thinking that you could have or should have done something differently. I could have been one of the women who ‘simply smiled at you, shook their heads and walked on’ when you approached them about the sexual abuse. Thank you for believing me now, for understanding that sexual, spiritual and institutional abuse are complex and for not shaming me for not recognizing what was happening to me at the time.

I’ve been thinking that AY teachers who want to continue to venerate Pattabhi Jois and teach yoga adhering to his tradition/lineage/method ought to call it Vinyasa Yoga (honesty in advertising). And teachers like you and Monica Gauci and others are much more deserving of the label Aṣṭāṅga (8 limbed) Yoga teachers.